A couple of things happened to me over the past few days as I was taking on a new role within a new project that caused me to ponder a bit about the role of domains and domain driven development (DDD) within the drive towards service oriented architectures (SOA). The result of these ponderings was, as it often is in my case, that the more we think things change, the more they stay the same. And the more we think we learn, the more we find we already knew what we have learned.

The first thing…

The first thing that happened is that I moved to my new project and found myself in a discussion about dealing with the consequences of earlier choices about how to deal with the overall application domain in the context of an application that will exist of a number of different, independent components composed using Web Services. As you will have already guessed, my new project is trying to implement a SOA (with service components that will later be part of a larger SOA).

The situation the project was in had developed from an attempt at implementing SOA by the book (in a somewhat reversed style). As we all know by now, the main tenet of SOA is that it allows you to take specialised components that deal with a single task well and combine them into larger services or applications with business meaning. Of course one might also reason (as my new project had done) that this means that you can take the specification of a new application and decompose it into functionally separate and specialised blocks. Implement these separately and compose them using web services et voilá: instant SOA.

To ensure that the different components would fit together (especially when communicating over the wire, but in general as well) it had been decided that all XML schemata and all implementation classes would be derived from the overall, conceptual domain model. Specifically, the model would be captured in a single set of implementation classes and shared across all the different components. The same model would be reflected in the XML messages passed between components.

When I arrived the project had become embroiled in problems related to tight coupling of its independent components. On the design side the use of a single domain meant that each component had to compromise in how well elements from the domain were suited to its purpose. On the implementation side, using a single domain package in all components meant that every change in any one component meant a rebuild and redeployment of all components.

The second thing

The second thing that happened was a discussion I had with a colleague about an MSN message he had written. He had used the word “enthousiasts”, after which I chided him about speaking “Nenglish” (English mucked up with Dutch influence). A search through a diary proved that he was correct, enthousiasts is perfectly good English — in British spelling.

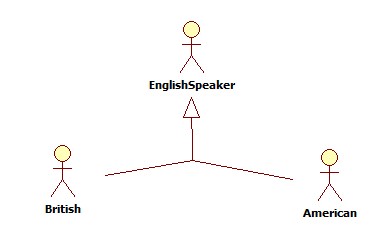

It took a little time for it to sink in that, even though he had misspelled the word in my eyes, I still knew what he was talking about. Even though it wasn’t my spelling, the concept of what he was saying had rung a bell in my head. One might model the situation like so:

What is illustrated by this diagram is that two people can speak different dialects of the same language yet share the meaning of words and concepts. They each have a language of their own, yet somehow both also “know” a second language that both share, speak perfectly and can use to communicate relatively flawlessly.

So what does this teach us about SOA?

The two situations described above teach us an important lesson about the role of domains and DDD when implementing a SOA: each component within a SOA has to deal with multiple domains, should be aware of this and should be allowed to do so.

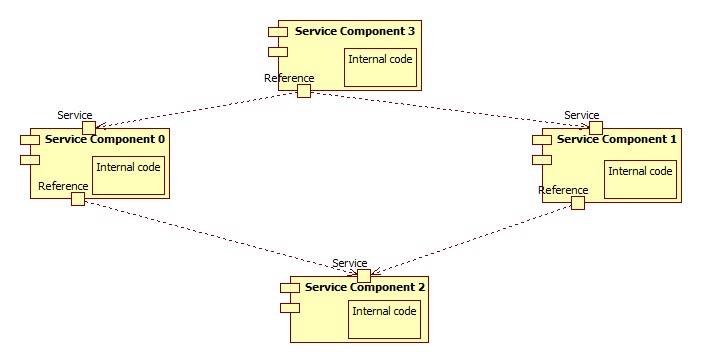

A typical component in a SOA has a number of connections to components in the outside world. This is because a typical component in a proper SOA does a single task and does this well and is therefore of interest to other components within the same SOA. And of course, the component itself might use other components to complete its task, for the same reason. So let us say that a given component offers N services to the outside world and references M other components. I then claim that the component has to deal with N + M + 1 different (but obviously related) domains, N + M + 1 separate languages. N languages that it shares with its clients, M languages that it shares with its referenced components and one more: its internal domain that it uses to do its job so well. In practice of course not all these languages will be distinct (or at least not completely); there may be overlap or shared communication languages. But conceptually N + M + 1 is the number and this fact should not be feared but rather respected. After all, it is this fact that allows components within a SOA both to be efficient and proficient at their own tasks, yet interoperate with other components at the same time.

Developing a single component within a SOA is all about performing a single task and doing that right, then passing the results on in a usable form. In that respect SOA is just a reinvention of the Unix command line tools. Tools like sed, grep, ls and so on don’t all do the world — they do one thing, do it well and allow their results to be piped in to the next tool in the chain. At the same time, no single tool cares about how the previous tool reached the results it did — just that it did. SOA components are much the same.

It is at this junction that we reach DDD. Each SOA component deals with a single, solitary, complex problem. A problem no other component in the same SOA deals with, nor should. DDD teaches us that complex problems should be based on a domain suited to solving that problem and that that domain should be the primary focus of the component. The component should care about how to solve its own problem well; it should not care about what anybody else is doing beyond the extent of getting needed data and passing it on.

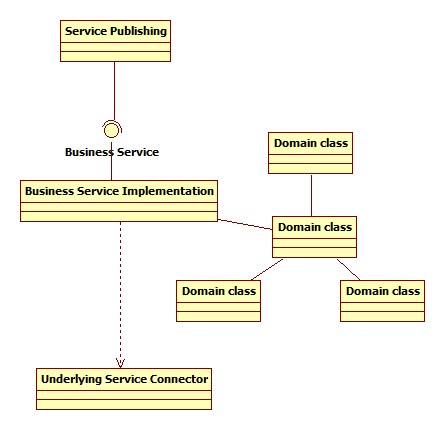

Moreover, DDD teaches us that the domain is divided into a number of different pieces. One of these pieces is focussed strictly on solving the actual problem (this is called the core domain), the other pieces are ancillary to accomplishing the task at hand. Some ancillary pieces might focus on communication with other components whose focus is on other problems. Eric Evans refers to this as repositories or in the extreme anticorruption layers (which prevent one model from leaking into another). It is therefore not at all unusual to see a structure within SOA components as illustrated on the right.

The figure on the right illustrates a SOA component, which offers a business service. This service is accomplished by leveraging a specialised domain model, tailored to the problem at hand. At the same time the component does not live in isolation — it is published to other components and connected to underlying services. But the publishing and the connecting are not part of the component’s core domain; these task are undertaken by ancillary components. And a prime task of these ancillary components is to translate between the component’s own domain model and that used to communicate with other components. Let there be no mistake, these are anticorruption layers in the literal sense of the term: they allow component to be specialised and service-specific domains to exist in isolation without being corrupted by the needs of the domain of every other component in the same SOA.

Of course that does not mean that each domain of each component within a SOA is completely unrelated to all others. There will by necessity be overlap in the concepts that are captured by two communicating components. However, in order to allow for an optimal solution to the individual problem addressed by a component it is necessary for that component to have full freedom in how it embeds that shared concept within its own domain and how much weight it carries within that internal domain (one man’s priceless is another man’s worthless after all).

At the same time a SOA component is completely worthless if it cannot communicate. It must therefore be able to deal with the communication domains that it shares with other components (the first step in moving from the domain of one component to the domain of the next). The techniques that DDD teaches us for dealing with communicating domains are therefore essential to building SOA components that strike the right balance between interoperability and optimized problem solving.

And so, once again, we see that moving to a new technology and a “new” architecture is no reason to forget everything we have learned. In fact, if anything, it shows the importance of recognising “new” ideas for what they are. If you know which wheel is being reinvented, you know which tools you must reinvent to make it run properly as well.

Reference: Domain Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software